Fad diets come and go but the Paleo diet has been around for over a decade. If the media attention it garners is an anything to go by, its popularity shows no signs of waning. However, the media coverage usually focuses on anecdotes from celebrities or must try Paleo friendly desserts and not so often on scientific evidence. So when I saw a headline last week referring to a clinical trial, I was curious to see what the data said. The study in question was published in the peer-reviewed journal Nutrients and described an intervention comparing the Paleo diet to the recently revised Australian Guide to Healthy Eating.

Paleo Diet vs. Australian Guide to Healthy Eating

Like other national government guidelines the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating are evidence-based dietary recommendations designed to promote health and prevent chronic diseases in the general healthy population by encouraging appropriate choices from the 5 food groups (1. vegetables 2. fruit 3. grains 4. meat, poultry, fish 5. milk, yoghurt, cheese and alternatives).

In contrast, Paleo is an abbreviation for Paleolithic, meaning that this diet aims to emulate the eating habits of our hunter-gatherer ancestors and therefore excludes all foods that are products of agricultural farming or processing. The working hypothesis is that our digestive system has not evolved to cope with our modern diets leading to the observed increase in chronic diseases such as diabetes. Thus, the diet promotes consuming meat, fruit and vegetables while prohibiting all grains, dairy, sugar and processed foods. A handful of studies have evaluated the impact of the Paleo diet on health with some positive results. But nutrition experts raise concerns over its long-term sustainability, and potential nutrient deficiencies arising from avoiding specific foods. For a more comprehensive summary of the Paleo diet and comparison with the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating recommendations check out this recent review published by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners.

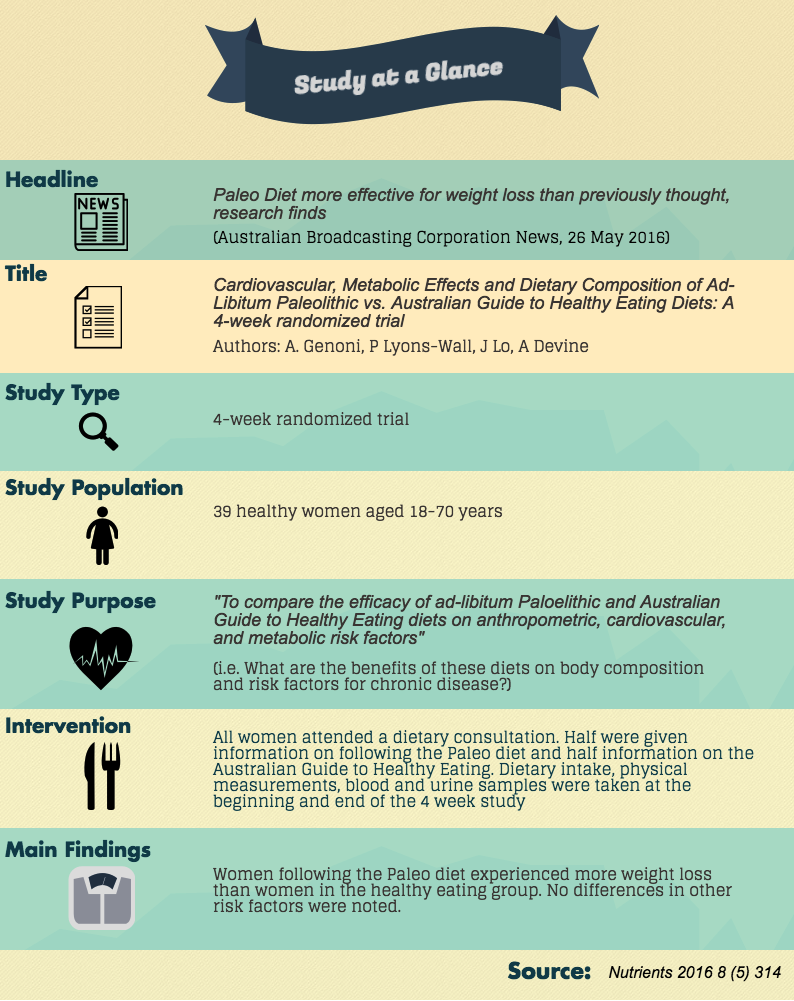

The study behind the headlines

How was the study conducted?

42 healthy Australian women who demonstrated a willingness to change their dietary habits were recruited into the study (3 later dropped out leaving a total of 39). At the beginning of the study, all women attended a dietary consultation and were provided with advice in accordance to the dietary group they had been assigned (i.e. Paleo or Healthy Eating). All women were free to eat as much as they wanted. During the 4 weeks of the intervention, the researcher contacted them weekly to offer support and advice. Compliance with their assigned diet was assessed via a daily food checklist. At the beginning and end of the study, all women completed a 3 day weighed food record and received a health assessment that included physical measurements (e.g. height, weight, waist circumference, body fat percentage), fasting urine (e.g. sodium) and blood samples (e.g. cholesterol, glucose). The researchers then compared the changes in these measurements between the 2 groups.

What were the results?

Over the 4 weeks of the study, women in both groups lost weight but women following the Paleo diet lost 3.2 Kg which was statistically significantly more than the 1.2Kg lost by women following the healthy eating guidelines. Waist circumference and body fat mass was also decreased in both groups (3.4cm vs 1.6cm and 1.5% vs. 0.14%, respectively) but again the loss greater in the Paleo group. Both groups experienced a reduction in total and LDL cholesterol but the difference between groups was not significant. There were no other differences in biochemical measurements. Total energy intake decreased in both groups but the reduction was significant in the Paleo group, this was due to the observed reduction in carbohydrate intake. Fibre intake did not change in either group. Saturated fat intake decreased in both groups. Compared to the healthy eating group, the Paleo group had lower intakes of calcium, sodium, iodine, and higher intakes of vitamin E, vitamin C and beta-carotene.

What does this all mean?

Overall, the study found that in the short-term, the Paleo diet resulted in greater weight loss compared to following healthy eating guidelines in a small group of healthy women. But did not find evidence that it was ‘healthier’ in terms of risk factors for chronic disease.

So, if you’re thinking Paleo might be the way to go to reach your weight loss goals then I’d add ‘hang on to your horses’! After reading this journal article I have a few reservations……

First, the aim of the study was not weight loss, in fact it was very general. “To compare the efficacy of ad-libitum Paloelithic and Australian Guide to Healthy Eating diets on anthropometric, cardiovascular, and metabolic risk factors”, sounds very fancy and is an important overarching goal but when conducting a study this objective is far too vague. The researchers aimed to see which diet was most beneficial for health but what exactly does ‘beneficial’ and ‘healthier’ mean? It would have been much more useful (and scientifically rigourous) to have articulated a specific hypothesis with a single primary outcome and measured the other variables as secondary endpoints.

Second, the authors conclude that the Paleo diet ‘induced a more favourable effect on body composition’ but this was a group of healthy women with a mean BMI of 27Kg/m2, waist circumference of 85 cm, and at low risk of chronic diseases. Some of the women would have already been classified as having a healthy weight so weight loss would not be a desirable outcome for them. After all weight is not equivalent to health.

Third, interventions aiming to change dietary habits are difficult to study because human behaviour is complex! The women who volunteered to be a part of this study on diet may have had a greater interest in health than the general population and therefore may have already been consuming a balanced diet. Also the action of monitoring a persons’ food intake can influence what and how much they eat. For example, the act of needing to complete a daily food checklist for a month may have led some women to avoid eating certain foods so they didn’t have to record it!

Fourth, the article failed to provide valuable data on the dietary assessment, dietary consultation, and the women’s personal experience. Some of the questions I had were:

- Who conducted the dietary consultations? What was their training? How long was the dietary consultation?

- Were the dietary consultations tailored to the women’s current intake? i.e. the authors state that the healthy eating group were advised to ‘increase fruit and vegetable intake and reduce fat intake’ but did they need to do this? It would have been interesting to have seen the data on actual food groups consumed before and after and not just the macro and micronutrient intakes.

- What were the women’s perceptions of the respective diets? Did they find the changes difficult/easy? What knowledge about the diets did they retain after the consultation? Did they experience any physical symptoms? Did they observe changes in their perceived energy levels/bowel habits/satiety/wellbeing/quality of life?

Fifth, I had other concerns about the steps taken to reduce potential bias that were not discussed in the paper such as the method of randomization (sealed envelopes) not being optimal, the validity and reliability of the checklist for assessing dietary compliance, whether the statistical analysis was blinded, and whether the observed changes were clinically significant. Together these issues bring into question the overall quality of the study and reliability of the results.

Should I believe the headlines?

The headline was correct in saying that the study found that the Paleo diet was effective for weight loss but this is nothing new, other studies have observed the same (likely due to the exclusion of 2 food groups). Furthermore, weight reduction was not the primary purpose of this study. All the studies to date, including this one, have looked at small numbers of people and are short in duration, therefore, the quality of this current evidence is weak; larger longer term studies (i.e. years) are required to truly determine its impact on health and chronic disease.

So yes, it may work for short term weight loss but in the long term being Paleo demands proper planning to ensure a healthy weight and an adequate macro and micronutrient intake is maintained. As always, you should look beyond the headlines and wait patiently for more data to emerge!

Gabriel Blazes says

Gabriel Blazes says

July 28, 2016 at 5:12 amNice content Naomi, very informative! I love the way you specify every details in the Paleo diet and the healthy eating guidelines . From reading the article, I would agree with the conclusion that Paleo diet is more effective than the other one. And let’s talk about the way you compare the two diets, awesome! I’ve wrote an article about Paleo and added 4 benefits on it, too. You might want to check it out.

Don’t hesitate to get back to me on the comment section of my article and we can share some ideas about Paleo. 🙂

Christopher Eagle says

Christopher Eagle says

November 12, 2024 at 12:29 pmThis is some awesome thinking. Would you be interested to learn more? Come to see my website at 46N for content about Thai-Massage.